Among the many reasons why people visit their doctors, two of the most common involve pain.

Joint inflammation and back problems — two frequent sources of acute and chronic pain — are more common in women. In fact, 70 percent of chronic pain sufferers in the United States are women, exposing women to risks that go beyond physical and mental discomfort. Such risks are incurred because the most regularly prescribed treatment for pain is opioids, which have helped to fuel an addiction epidemic that affects more than 2 million Americans and kills an estimated 130 people every day.

Over the last two decades, more than 200,000 Americans have died from prescription opioid overdoses, and the risk to women has been accelerating. Women are currently more likely than men to be prescribed opioids. Further, women are more likely to be prescribed additional medications that increase the likelihood of an opioid overdose. Between 1999 and 2016, overdose deaths from opioid prescriptions increased by 583 percent for women — a rate 179 percent higher than for men.

Women’s Health Research at Yale is confronting this problem with two new studies to investigate and potentially transform the treatment of pain with alternatives that avoid the inherent risks of opioid medications.

“I have witnessed family and close friends suffering from chronic pain, and often the medications they are prescribed do not seem to relieve their symptoms enough for them to function normally,” said Dr. Irina Esterlis, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Molecular Imaging Program for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD. “I have also seen people close to me stop their pain medications because of unpleasant side effects or because they feared addiction, sometimes hindering their recovery.”

A Promising Molecular Target to Reduce Pain

With this year’s Wendy U. and Thomas C. Naratil Pioneer Award, Esterlis is studying a promising biological target to see if it might offer a non-addictive alternative to relieve chronic pain in women.

“We must develop new ways to effectively treat chronic pain without the risk of addiction,” Esterlis said. “Our study will provide vital insights into the biological and chemical mechanisms behind chronic pain with tremendous promise for a type of therapy that can help people — particularly women — return to normal functioning within their careers and families.”

The cells of the central nervous system communicate with each other like a game of telephone in which one cell shares a chemical message with the next. Protein structures that reside on cell surfaces called receptors act like locks that only function and pass on messages when the correct chemical key is inserted. The more receptors that are available on the surface of cells, the more keys that can be inserted, resulting in a more intense or long-lasting message, such as increased levels of pain. Medical interventions targeting specific receptors have the potential to calibrate these messages so that they are relayed properly and achieve desired health outcomes, such as decreased pain.

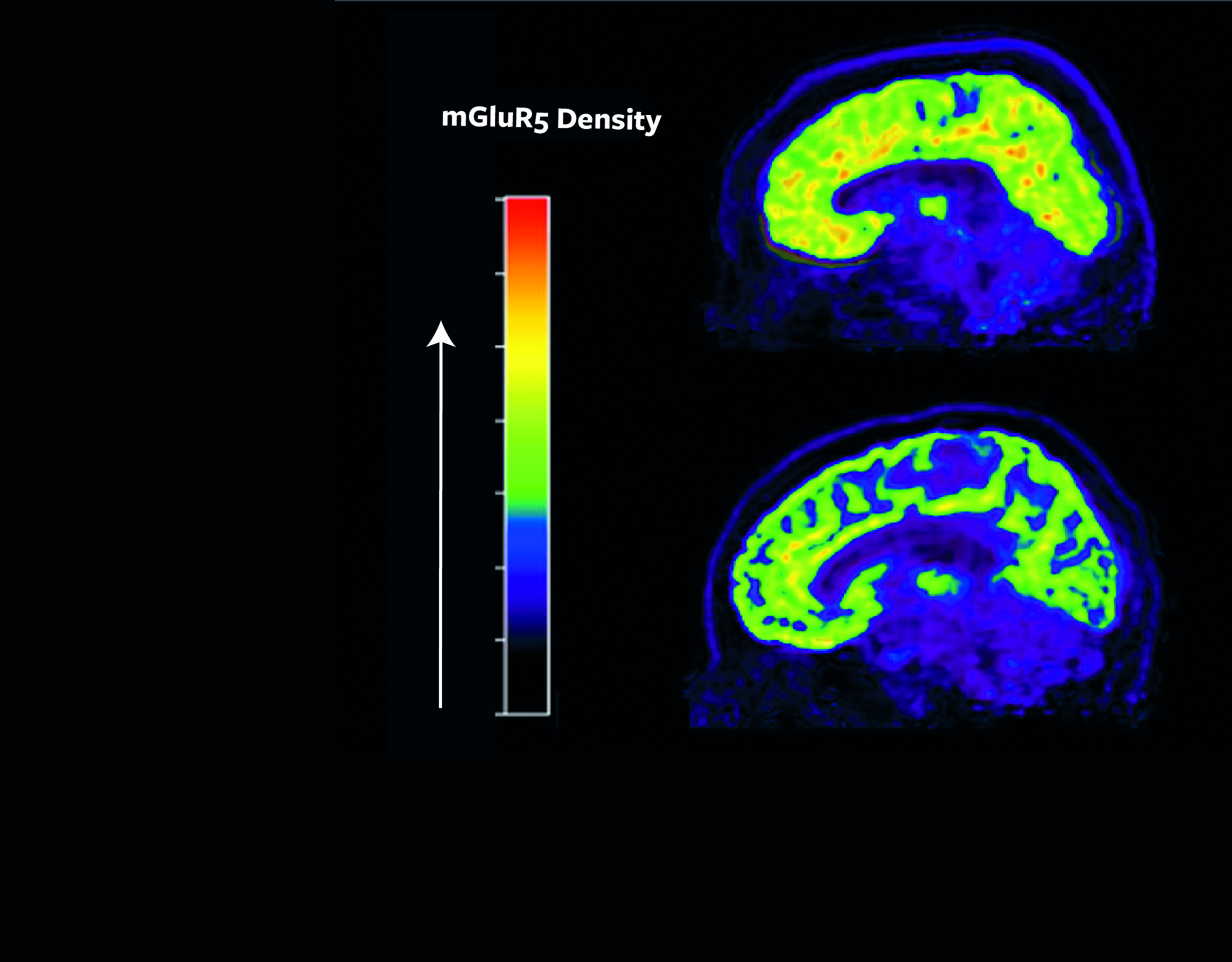

One particularly versatile and influential receptor is known as metabotropic glutamatergic receptor 5 (mGluR5), which has been shown to affect mood, sleep, cognition, and learning. Many studies in animals over the last decade show higher levels of mGluR5 associated with the sensation of pain. In addition, experimentally lowering mGluR5 availability appears to decrease pain in both female and male animals.

In a study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in June, Esterlis and her co-authors studied people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who also had suicidal thoughts and found these individuals had more mGluR5 receptors available to receive chemical messages at the cell surface (termed “mGluR5 availability”). This finding led Esterlis and her team to consider whether altered levels of mGluR5 availability may also be crucial to our understanding of pain regulation given the relationship between pain tolerance and suicide attempts.

Using similar techniques employed in the study of PTSD and suicidal thoughts (see image above), the researchers will examine brain images using positron emission tomography (PET). Now they are looking to see if women and men with chronic lower back pain have higher mGluR5 availability as compared to people with no pain and determine what differences might exist between the sexes.

Previous research has already demonstrated that women and men experience pain differently. For example, premenopausal women have more difficulty managing pain compared to men in the same age range because of naturally higher levels of the hormone estrogen. Conversely, testosterone is more prevalent in men and has a protective effect against feeling pain.

“There is so much more we need to understand about the biological mechanisms behind the sex-and-gender differences we observe in the experience of pain,” Esterlis said. “Particularly because women generally feel greater pain intensity and over longer periods of time, treating women with higher doses of opioids increases health risks dramatically, including infertility, cardiac events, and overdose.”

Esterlis will use preliminary data generated from this study to seek additional funding for a larger study to test pain reduction using an existing medication that lowers mGluR5 levels.

“This is the next logical step in my work,” said Esterlis, who began studying the influence of mGluR5 on smoking and mood disorders before moving on to study suicide and now pain. “It’s all related.”

Cannabis, Pain, and the Brain

Currently, 34 states permit the medical use of cannabis, a swath of the country that covers more than two-thirds of the total population, more than half of whom are women. In addition, there will soon be 11 states that allow adults to use cannabis recreationally, granting greater accessibility to the drug without medical supervision.

In 2017, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a report on the health effects of cannabis. A committee of experts conducted an extensive review and determined there are only three health conditions for which there is currently either conclusive or substantial evidence of cannabis’ effectiveness as a treatment. These include relief from chemotherapy-induced nausea and improved patient-reported multiple sclerosis spasticity. The third use, supported by strong evidence, is pain relief.

In fact, 65 percent of medical cannabis users in the United States cite chronic pain as their qualifying condition when seeking the drug. But there is so much more we need to know, particularly about the relative risks and benefits of treating acute and chronic pain with cannabis. Further, while women are increasingly in need of safe and effective pain relief, we know very little about how cannabis might affect women and men differently.

Previous studies tell us that among frequent users of cannabis, women report less pain relief from the drug compared to men, possibly a sign of greater tolerance and lower effectiveness over time. In addition, women who use cannabis frequently progress more rapidly than men to problematic use. Thus, it is possible that cannabis may pose a greater risk to women with less benefit, a finding that could have great significance for health care decisions and public policy.

With the support of WHRY, Dr. Ansel Hillmer, Assistant Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging and of Psychiatry, is examining the effectiveness of cannabis in pain relief and investigating if there are any differences between women and men.

Dr. Hillmer will use brain imaging techniques to better understand the molecular mechanism by which cannabis dulls pain. He and his team will employ PET scans to observe how the drug affects the brain’s process of producing and using what are known as endogenous opioids, naturally occurring chemicals such as endorphins that inhibit the communication of pain signals and can produce a feeling of euphoria similar to that of prescription opioids.

Previous research has shown that cannabis triggers the release of endogenous opioids when the main active ingredient of the cannabis plant, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), binds to specific opioid receptors in the brain. Dr. Hillmer’s team is injecting a safe radioactive biochemical into subjects that binds to a particular receptor called µ-opioid receptor (MOR), which will allow them to measure the level of opioid response via PET scan. They will measure the opioid response both before and after smoking a federal government-supplied cannabis cigarette. Dr. Hillmer and his team hypothesize that women will show a smaller opioid response to cannabis smoking than men, as observed by smaller change in radioactive signal, which could signify that the use of cannabis for pain relief in women may be less effective than for men and that other options should be explored.

In addition, Dr. Hillmer’s team will investigate the ability of cannabis to reduce pain by conducting tests of pain tolerance and sensitivity before and after smoking cannabis. They predict that women will experience less pain relief than men after smoking cannabis because of the hypothesized lower neurochemical action of the drug. These tests, along with the PET imaging, will help determine how the neurochemical response to smoked cannabis is linked to the physical sensation of pain. Hillmer anticipates that the study will also produce data for a larger external grant to better characterize the effects of chronic cannabis exposure in women and men.

“We are working toward better, more individualized treatments for pain relief,” he said. “That means taking into account the specific risks and benefits of medical cannabis for women and men.”